Please click this link for book and purchase information

COVID-19 piqued my interest in the Spanish flu, which devastated the world from 1918-1920. This led me to place library holds on several e-books about the subject. The first one available was

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish

Flu and the First World War by Kenneth C. Davis. This short book, aimed at young adult readers, turned out to be an excellent primer on the pandemic. It taught me a lot I didn't know.

The Spanish flu was first noticed in Haskell County, Kansas in January, 1918. Two months later an outbreak appeared in a Kansas army training camp. More outbreaks erupted at other camps in the United States as the country prepared to enter World War I. US troops brought the disease to Europe and passed it on to other allied soldiers and civilians. German soldiers picked it up from allied prisoners they released.

|

| Crowded sleeping area at Naval Training Station, San Francisco, California |

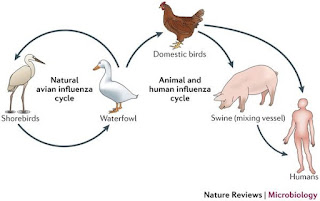

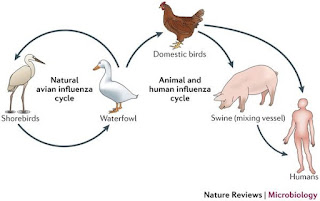

Both sides in the war supressed news reports on the disease, to keep up morale and not let the enemy know their troops were weakened. Spain was neutral in WWI, which freed journalists to broadcast reports on the new disease striking their fellow citizens, including the king of Spain. The name Spanish flu stuck. To this day, Spain would like that error fixed. I might suggest calling it the Kansas flu pandemic, but the World Health Organization now recommends that we no longer name diseases after places to avoid the negative effects on nations, people and economies. To add to the controversy, some researchers speculate the Spanish flu originated in France, China or the eastern USA. Recent studies on recovered samples of the virus suggest it was initially transmitted by a bird.

Unlike most viruses, the Spanish flu, H1N1 influenza A virus, attacked a disproportionate number of healthy, young adults. One theory for this is that their strong immune systems overreacted. Another is that an earlier strain of the virus gave many in the older generation immunity. It's now estimated that the Spanish flu's four waves killed close to

100 million people worldwide , about 1/20th of those alive

at the time. It is history's second most lethal pandemic, after the Black Death.

Sprinkled through More Deadly Than War are stories of historical figures who contracted the disease. In addition to the Spanish king, Walt Disney and artist Edvard Munch recovered. US President Donald Trump's grandfather was an early victim. According to the family account, Frederick Trump was walking down a New York City street, when he suddenly took ill. He died the next day. The cruel virus tended to act swiftly. Some called it the three day fever.

|

| Was Edvard Munch's agonized painting "The Scream" partially inspired by his suffering from the Spanish flu? |

The primary advice in 1918 for escaping the Spanish flu sounds familiar to people living through COVID-19 today.

- Wash your hands.

- Maintain a social distance.

- Avoid crowds.

A friend sent me links to my home city Calgary's history of the Spanish flu. We know the precise day the disease arrived - Oct 2, 2018, when a train from eastern Canada brought patients to Calgary's isolation hospital. Unfortunately, the measure didn't isolate the disease from Calgary residents. An estimated 38,000 people in our province of Alberta contracted the Spanish flu; 4,000 died.

|

| Poster in 1918 Calgary, courtesy Glenbow Museum |

Will my interest in the Spanish flu filter to my fiction writing? I'm mulling potential ideas for my next Calgary mystery novel.