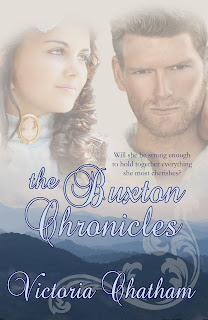

TO BE RELEASED IN DECEMBER

WATCH THIS SPACE

In the Regency era, the hand fan was so much more than a fashion accessory or a cooling device. It had an art and language, all of its own, not only known to ladies but gentlemen too.

The fan with which we are familiar today has been around for thousands of years in one form or another. At its simplest, it could be just a large leaf or palm frond. At its most extravagant the sticks could be made from

The Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians used them, two fans being found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. The Chinese use of the fan is reputed to date back to the Shang Dynasty (C.16th-11th BC). At first, the fans were large enough to shelter passengers in horse-drawn carriages, similar to an umbrella. It wasn’t until Song Dynasty (420-479) that the personal fan came into general use. These fans could be simple bamboo fans, or the moon fan so called from its round shape. These moon fans were much favored by ladies in the Imperial court and came to be painted with the most exquisite scenes of mountains and lakes, flowers, and birds.

The folding fan is reputed to have been introduced into China from Japan during the Song Dynasty. The design is said to have been inspired by the way a bat fold’s its wings. The size of a folding fan is determined by the number of ribs the fan has, usually 7, 9, 12, 14, 16, or 18. A fan painted by a famous artist could fetch a high price, as did the folding fan painted by Zhang Daqian, a Chinese artist, which sold for HK$252,000. The earliest evidence of the fan in Japan was discovered in the wall paintings of a 6th-century AD burial mound found in Fukuoka.

Fans were not much in evidence during the High Middle Ages in Europe but reappeared after being brought back from the Middle East by the Crusaders and from China and Japan by Portuguese traders. The fan became especially popular in Spain where it was adopted by Flamenco dancers. In 1609 The Guild of Fan Makers was formed in London, followed a century later by the Worshipful Company of Fan Makers. Although no longer fan makers, due to mechanization, the Company still exists as a charitable establishment.

During the Regency and Victorian eras no lady of quality would attend a social event without her fan with which she could hold a lively conversation without saying a word. For a list of the language of the fan, go to http://www.angelpig.net/victorian/fanlanguage.html or https://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2008/07/24/ladies-regency-fans/ or just for fun watch this clip from The Princess Diaries 2 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8bE3mRxWwM4.

Quite apart from the social etiquette surrounding the use of the fan, they were favored by burlesque and vaudeville performers such as Gypsy Rose Lee, who teased and titillated with large, ostrich feather fans.

Arguably the largest organization in favor of the fan today is FANA – Fan Association of North America which boasts worldwide membership. Like-minded members study, conserve, and collect antique and vintage fans.

You may wish to flirt with a fan or cool yourself with it. You can use it as a decorative conversation piece. Whatever your use for it, there really is nothing quite like the seductive allure of these fascinating concoctions of sticks and fabric.

http://victoriachatham.blogspot.ca

.jpg)